I am

heartbroken. I am preparing to leave for Costa Rica this afternoon but had to

write this before I got out of here. I owe my champion that much.

Muhammad

Ali gone. I’m trying to wrap my head around this loss. This loss of not just a

sports icon, although surely he was that; not just the loss of one fine brutha,

because he was undeniably that too; not just the loss of a political lightening

rod because lawd knows he fit that bill; but the loss of an era because he

represented the best of a time that was so affirming for so many of us African

people.

Muhammad

Ali burst on the scene as a young, brash, self assured sho nuff brother at a

time when Black people all over the world so needed a voice that spoke loudly

and confidently. His metamorphosis from Negro to Black represented that of an

entire Black World and in so many ways helped us all stand a little more firmly

on a Black ideological platform. As a striving artist trying to define a Black

aesthetic in my work, I know I felt a certain kinda way looking at this fine

black brother stand up to the white power structure and refuse to fight their

war. I know I puffed up just a little more when he refused to be subservient to

the white journalistic world and spit back at them retorts that made their

heads spin, never letting them put him in some “dumb boxer” box. I can still

recall how proud I felt that this King of the athletic world wasn’t afraid to

have strong political views that didn’t include kowtowing to white folks and

extolled loving your blackness because all of us needed to be reminded of this

daily in order to stay strong in racist America.

Muhammad

Ali was a complex man; a man who many didn’t realize was a latent artist. Like

his father, he loved making art, and like his father, was never directed/allowed

to follow that path. I wonder what would have happened had he been encouraged

to follow his talent in art rather than boxing. According to his biographers,

art and physical education were the only two subjects he did well in as a

student in school (I suspect he had dyslexia, a learning difference that didn’t

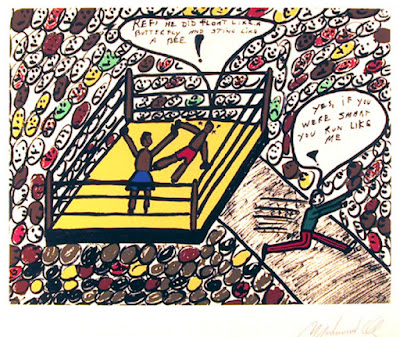

get much attention until long after Ali had graduated). When I saw some of

Ali’s work a while back it was evident that he had a keen eye for design and

color and his comical piece depicting the epic Ali-Liston fight had a nice

political bite, I couldn’t help but to wonder if Ali wouldn’t have been at the

forefront of the Black Arts Movement were his art aspirations realized. I saw

an interview with artist Layla Ali (no relation to Muhammad Ali but ironically

having the same name as his daughter albeit spelled differently) where she

explained her need to make art. She said, and I’m paraphrasing, that

essentially she had to make sense out of the electrical/spiritual energy that

was rolling around in her head vis-à-vis artmaking or someone would get

hurt! What would have happened if

Muhammad Ali had made that journey into his creative energy persona rather than

his athletic energy persona? I wonder if his world of hurting someone

physically would have been one of hurting someone psychically?

I know this is a conversation that is veering way off the course of talking

about Muhammad Ali’s life as a Black Icon, but is it really? When I think of the power of art to shape

society, I think of why so many African people are never encouraged to follow

that path. I think of how young Black boys throughout urban America (who are

just like young Cassius Clay) can demonstrate ability in the arts but not have

that cultivated in favor of pumping them up as athletes. I think how they can

be used as athletic pawns in the game of professional sports only to be

discarded once past their prime, and left with nothing to renew their humanness

so they self-destruct. Muhammad Ali was

one of the lucky ones in so much as he at least wasn’t left broke at the end of

his usefulness to the sports world. But he was left physically broke and in

some ways was defanged because his ability to articulate verbally was no longer

possible and his disease rendered him incapable of pursuing his creative side.

What would Muhammad Ali the painter be telling us if he were articulating the

political views of the Ali I so love? How potent would his visual messages be

to us about what it means to be Black in a time when #blacklivesmatter is the

hashtag of the era? Granted, he may

never have reached the worldwide stage as an artist and therefore not gained the

platform to influence in the way that he did as an athlete, but I can’t help

thinking that someone with his charisma and self-assuredness would have made

his mark in a big way, no matter what the limitations inflicted by the

so-called mainstream artworld.

Vicki Meek is a retired arts manager, a

practicing artist and activist splitting her time between Dallas & Costa

Rica. She writes a blog Art & Racenotes and a column ART-iculate for

TheaterJones.com, both exploring issues around race, politics and the arts. Contact

her at www.art-racenotes.blogspot.com.